Swiss watchmakers and the Ottoman market

On 14 May, Sotheby’s will present « Century of Time : A private collection » in Geneva, a not-to-be-missed event that brings together historic and extremely rare timepieces the likes of which the market has not seen in over 10 years!

With more than 100 wonderful pocket watches, this collection tells one of the most beautiful chapters in the great history of watchmaking: the Ottoman Empire’s and Asia’s consuming passion for European watchmaking in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Mainly composed of watches produced for the Ottoman and Chinese markets between the 16th and 20th centuries, this collection, assembled by an enlightened amateur, takes us back to the golden age of watchmaking.

Each watch is a real concentrate of history: the history of watchmaking techniques and know-how, the history of tastes and styles, the history of trade and exchanges between countries, and the history of diplomacy.

The rise of the Ottoman market

Amongst the most spectacular pieces, several 19th century watches made especially for the Ottoman market are by far the most fantastic items in this sale.

It was in the 16th century that the Ottoman Empire developed a craze for Swiss watchmaking and the first Geneva clocks and watches were exported to Constantinople.

In “La Fabrique Genevoise”, a historical work on Geneva watchmaking published in 1938, the historian Anthony Babel traces the rise of the Ottoman market and the golden age of Ottoman watches:

“The scales of the Levant – Constantinople, the ports of the Aegean Sea and the whole of Asia Minor – also constituted a very remarkable market for our watches. The sale of our watches was so important in the eastern Mediterranean basin that their repair and sale led to the creation of an important Geneva colony in Constantinople. Its existence lasted at least two centuries.”

It is undoubtedly in the 19th century that the most beautiful pieces were produced. One of the most representative watches of this production is certainly the one signed Blondel & Melly . Denis Blondel and Antoine Melly, watchmakers active in Geneva between 1820 and 1850, produced a wide variety of colored watches, exclusively for the Ottoman market, which differ radically from the pieces produced for the European or Russian markets. Made of gold and always enamelled in bright colours, Blondel & Melly’s watches are often decorated with floral motifs, and sometimes set with fine pearls.

Particularly rare, indeed almost impossible to find on the market today, this signature rarely appears at auction. In 20 years, only three watches by these Geneva watchmakers have reappeared on the international market. The first was sold 22 705$ by Christies on 6 December 2002 in New York (lot 152), then sold a second time at auction by Sotheby’s for CHF 30,240 on 12 November 2010 (lot 575). The second was sold on 16 May 2011 by Christie’s in Geneva for CHF 57 500. Finally, the third (Photo 6) was sold for CHF 10,625 by Antiquorum on 11 May 2019 (lot 2).

Like the watch to be auctioned on 14 May, each of these pieces was stamped with the “FM” goldsmith’s mark on the case. Estimated at €20,000 / 30,000, this Blondel & Melly watch is extremely original, and stands out from the watches already listed by its decorations.

Note that their production is always numbered between 13000 and 20 0000, and that this watch is numbered 16158. To date, only a few watches are kept in public collections, one is listed in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York and another in the Wien Museum.

« Another Geneva in the East »

It was really from 1602 that Geneva and Constantinople developed close commercial relations. The first business trips were organised, and Swiss watchmakers travelled to Marseilles in order to reach the Near East by ship. From 1606, Switzerland became the main supplier of clocks and watches to the Ottoman Empire.

In Constantinople, the Palace and the great families of dignitaries represented for many artists and craftsmen a clientele in search of elegant furniture, rich bindings and precious objects of all kinds. For Swiss watchmakers – whose activities had been thwarted by the Protestant reforms prohibiting the wearing of jewellery and ostentatious signs – the Ottoman Empire was a veritable Oriental El Dorado.

In order to gain a foothold in this new and extremely lucrative market, which was also coveted by English and French watchmakers, some Swiss watchmakers set up a permanent presence in Constantinople and opened a branch office there. There they placed a “watchmaker” in charge of the adjustment and maintenance of the imported timepieces sold there. A real “Geneva congregation” was thus organised in Constantinople.

Like “another Geneva in the East”, Constantinople was to become one of the leading centres for the watchmaking trade. Although Swiss watches were imported in large numbers, watchmaking remained exclusively accessible to the sultans and a few high dignitaries.

Breguet, the greatest watchmaker of the Ottoman Empire

Breguet is by far the most refined and spectacular watchmaker. As opposed to the technical and innovative pieces for which he is adulated, Breguet developed a production of richly enamelled and finely decorated watches for the Ottoman market.

With the Napoleonic wars making trade with Spain, England and Russia impossible, Louis-Abraham Breguet set his sights on the Ottoman market in 1802. Counting among his clients Esseid Ali Effendi (also known as Galib Effendi), the first ambassador of the Ottoman Empire to France from 1797 to 1802, Breguet supplied the Ottoman Empire with several watches, as well as barometers and thermometers. The two men kept up a correspondence which revealed, among other things, that from 1803 onwards, the Ottoman dignitary demanded that the watches delivered be: in gold, savonnette or with a brightly enamelled double case, equipped with a white enamel dial with Turkish numerals and not Arabic or Roman. Breguet then developed a specific production, which integrated these aesthetic codes. Easily identifiable thanks to their richly decorated dials and cases, it is estimated that Breguet produced an average of 6 to 8 pieces per year until 1820.

This “trickle-down” production explains the enthusiasm of collectors for these very rare watches. One of the most beautiful pieces in the sale is a gold and red translucent enamel watch, bearing the number 1950 and sold on 6 May 1808 to “His Excellency Gallib Effendi, Ambassador”.

Particularly accomplished, this watch includes a mechanism with a grand and a petite sonnerie, an independent minute repeater as well as 5 hammers striking on 5 gongs! A real jewel of technicality that strangely resembles a watch of equivalent quality sold in 2012 by Sotheby’s. Also equipped with the same complications and decorated with a translucent red enamel, this timepiece, which bore the number 1090, was sold for CHF 650,000 at the time, making it the most expensive watch ever produced for the Ottoman market.

Emmanuel Breguet, who purchased the watch for the Breguet Museum, told the New York Times at the time that only 10 repeater watches had been ordered from Breguet by Galib Effendi after 1802. This information suggests the enthusiasm that this watch should arouse on 14 May!

Louis Auguste Courvoisier or the art of diplomacy

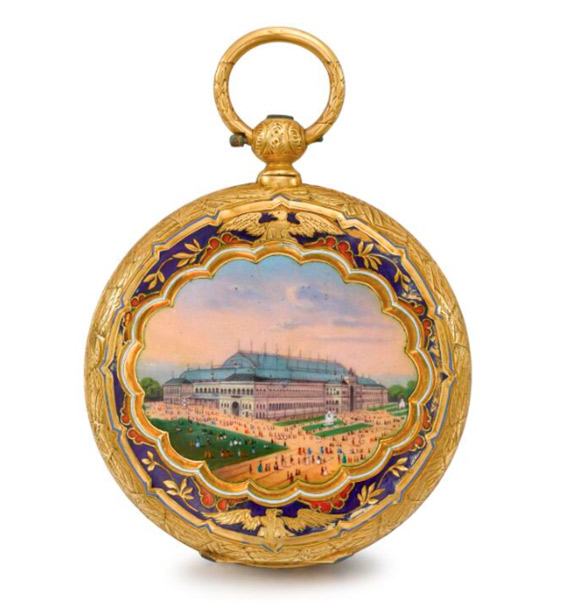

One of the most striking Ottoman watches in the “Century of Time: A private collection” sale is probably the one made by Louis Auguste Courvoisier and numbered 45396.

This enamel gold watch reveals on one side a miniature representing the Palais de l’Industrie in Paris, and on the other the portrait of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte.

Probably offered by Napoleon III to a dignitary of the Ottoman Empire, this piece reminds us that for several centuries the watch was, and still is in some countries, the diplomatic gift par excellence.

Produced around 1855, it is possible that this watch was offered in the context of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1856, which proclaimed the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and made the Black Sea a geopolitical trading area. Given the enamelled decorations visible on each side of the case, it is obvious that this watch was not intended to “tell the time”, but that its function was quite different.

Inaugurated on 15 May 1855 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the Palais de l’Industrie was built to house the first French Universal Exhibition. Since their purpose was more to publicise and immortalise this event than to tell the time, watches produced for the Ottoman market were also sometimes used to convey a political or economic message in the context of diplomatic exchanges.

The international reputation of Swiss watchmaking

Swiss watch production for the Ottoman market is undoubtedly one of the threads that have guided the constitution of this collection. Among the most beautiful pieces, these three watches are absolutely fantastic and tell the story of the Euphoria that Swiss watchmaking triggered in the Middle East 250 years ago.

It is in fact thanks to the Turkish sultans and high dignitaries that Swiss watchmaking acquired its international reputation!

Although the Ottoman market was extremely lucrative for Geneva and European watchmakers in the 19th century, it should be remembered that until the 18th century, watches were particularly rare in the Ottoman Empire, or even impossible to find, and watchmakers even more so! Moreover, in “Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte”, Volney deplores the fact that in 1784, “hardly a watchmaker who knows how to mend a watch can be found in Kairo, and he is European”.